I struggled to get out of bed that day. It felt like I was forced to perform a task which I was not being compensated for. I had also struggled to go to bed the previous night. My understanding of the nature of sleep is that it speeds up time, and when you have a doctor’s appointment the next day, you find yourself at war with the speed of time.

I opened my eyes and noticed that a new day had arrived. It started with the clucking sounds of chickens, followed by the loud bus noises, and finally, the sounds from taxis beeping their horns. Upon waking up, I felt like a coward forced to face his fears. The morning sun reflected through my window, brightening my room and making it light red to match the colours of my curtains. I noticed that my wife was still sleeping and, to avoid waking her, I sneaked out of bed slowly like a snake shedding its skin. I avoided switching on the lights.

It was a Friday, and my doctor’s appointment was at 9am. I’d booked the appointment a month before, when I started noticing that something was different about me. My family had also noticed that there was a great disconnect – between the man I normally was, and the man that I had suddenly become. When I’d booked the appointment, the doctor had told me to arrange counseling sessions for myself. A month had now passed, and I had received counselling and believed that I was ready for any outcome of my medical procedure.

I arrived thirty minutes early at the doctor’s office. I reported to the reception area, and I was directed to a bench lining the corridor. The place had white walls, white ceilings, and white tiling. It also had that distinct smell one finds in almost all hospitals; the smell of sterilization and sterility. The place felt tranquil, as tranquil as the notion that death is a peaceful place. I suddenly felt like I was there to collect my death certificate. The deep silence was occasionally interrupted by the ringing of the phone, and the voice of the receptionist answering it. A janitor, who had just finished cleaning when I came in, walked past me to and fro, listening to music audible through his earphones.

The doctor arrived a few minutes before operating time. He entered the office, looking as friendly and as professional as he had the last time I had seen him. He was a tall and slender man, and wore his white coat like it had been created with him in mind.

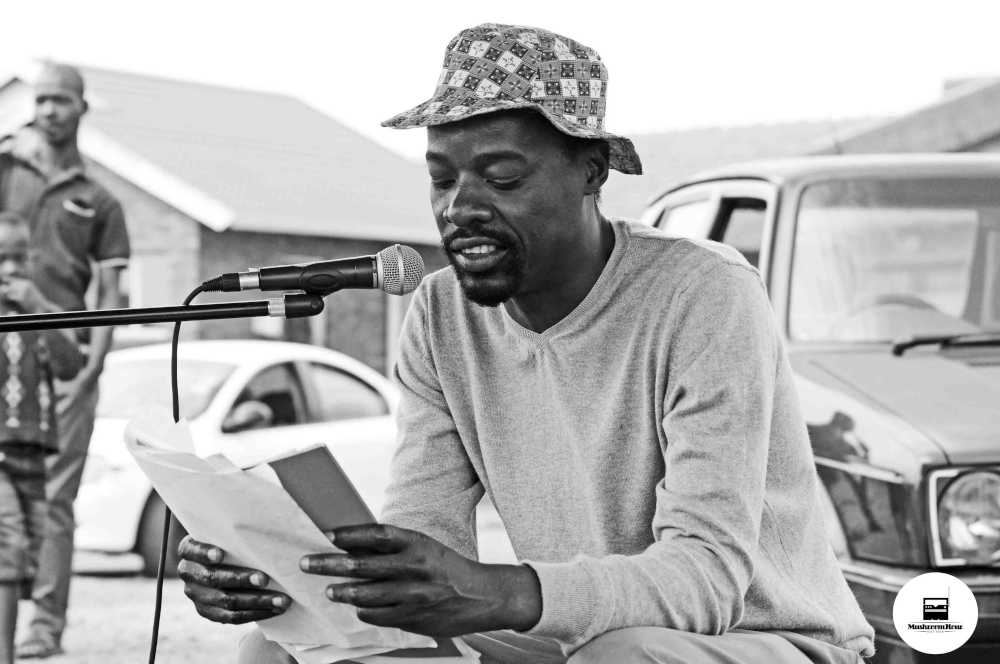

“Morning Mr. Mokoena,” he said to me smiling.

“Morning doctor,” I said.

“You can come in whenever you are ready,” he told me.

I followed him into his office and watched him as he prepared the machine needed for my diagnosis. He told me to sit on a chair, which he then further reclined, and moved the machine closer to me. The process started and to my amazement, it didn’t last long. I was astonished that a process whose results could determine how my life would unfold, could last this long (which is to say, this short). The doctor had a sombre expression on his face, as he analysed the results. He tried to conceal this expression by smiling and adjusting his glasses when our eyes met, but even beneath that smile and the professional kindness, I could read that my life was in danger.

He stopped analysing the results and looked at me briefly without saying anything, as though he was channelling the courage to tell me the results.

“I’m very sorry Mr. Mokoena, but the results came out positive,” he said to me. It was strange at that moment, how I was the “positive” one but something inside of me felt sorry for him. I felt sorry that such a genial man was tasked with the responsibility of being the bearer of such bad news.

“How much time do I have left to live?” I asked.

“I don’t know. It depends on the person, from case to case but I encourage you to make the best of your time.”

When I tried to stand up to leave the office, I realized that I couldn’t move. An overpowering, peculiar kind of emotional pain weighed me down, forcing me back onto my chair. It was the pain of denial. In my mind, I had thought that the counselling sessions had prepared me adequately, but this was evidently not true. I suddenly cried out, loudly, and began to sob without ceasing – like a baby with colic. My cries painted the plain white walls with sorrow, and I am certain that they also penetrated the janitor’s earphones.

I was brought some water, to relax me, and I was asked to call my family, to which I declined vehemently. I have personal experience with what happens to people who care for people with my condition. It affects the caretaker more than it affects the patient.

When I arrived home, I found my wife watching television. I avoided her and headed straight to my bedroom. I stared at myself in the mirror, and the image I saw reflected back at me seemed new, strange. The brown skin that used to look firm and youthful now seemed to hang a bit lower. It has so many lines, like when a child randomly drags a pencil on paper. The hair that used to be black now seemed suddenly tinted with grey hairs. The eyes that used to see the light at the end of the tunnel now could see nothing beyond the stark perception of my imminent death.

I moved from the mirror and took out a small notebook from a nearby drawer. I decided to use this notebook to tell the story of my life.

This is how my story begins. I was born in the dusty village streets of Makupaneng. The popular nickname of the village is “volcano” because of its severe heat. At times, it would get so intensely hot that we found it impossible to walk barefoot. I am my mother’s only child. After completing my grade twelve, I went to my local college to study to be a teacher, and this is also where I met my wife. When I met her, she was the most beautiful girl on that small campus and I loved her instantly. I remember that she wore a yellow dress that reverberated with the bright hues of the sun. She had short hair, and she smiled throughout our first conversation. We have been married for thirty years now.

After I graduated, I decided to remain in my village and teach at a primary school. I felt that I would be doing a disservice to my community, if I left to teach elsewhere. In my years of teaching, I have helped transform many children into becoming successful and responsible adults.

But I could not have been able to do this if it was not for my mother. She was a single parent but a day never passed where I slept on an empty stomach. She did everything for me, and even though I grew up in a world where television advertised things that one desired but could not have, I never felt that emptiness. In her love was embodied all the toys and gifts I needed.

My mother was skilled in knitting. It was her source of income, her business, and it is how she fed us. A lot of my school outfits were made by her. Her business thrived, and people in our village couldn’t stop talking about the quality of her work. From how she ran her business, I learned a lot about dealing with other people. She treated every customer with respect and equality. I learned from her that we see a person’s true nature by how they treat the people who are ‘lesser’ than them.

My mother died a few years after she was diagnosed with Alzheimer's. This is the same disease that I have, because of its hereditary nature. I watched my mother suffer in her final years, and this frightens me because I am going to suffer the same way.

As the doctor advised me to make the best out of the time I have left, I hope these notes will serve as a record of my life and special memories. Unavoidably, this disease will make me forget. Soon, I will not be able to recognise everything and everyone around me. I saw it in my mother and how she interacted with her environment. She moved from the superwoman that raised me, to a woman who could not do for herself. I was faced with a series of questions when I was taking care of her, and it is these series of questions that forced me to go to the doctor and find my answer.

Now that I have also tested positive for this disease, I know that ultimately there will be nothing familiar about my life except these notes. I hope that when my memories start to fade, and when my mind loses its amazing powers of remembrance, I can look back at this notebook and it will help me to remember who I am. I hope someone continues to record my memories. The memories I will not be able to record myself, because the disease will have taken my abilities by then. Those memories, still forthcoming, will be like the memories I created during my childhood-amnesia years. I hope that, on my way back to childhood, I continue to uphold the values I learned from childhood to adulthood.